Banking Structure Shapes Banking Ethics

By: Alex Zhihao Wang

Canada vs. United States

Past decades have exposed the fragility of the American financial system. The 1980s featured a series of banking disasters, ranging from the collapse of Penn Square Bank to the Savings and Loans Crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. The combined cost of resolving the S and L crisis totaled over 100 billion dollars (Amadeo). Even worse was the financial crisis of 2008. Falling housing prices caused a wave of foreclosures, thus precipitating a larger financial crisis that required a $700 billion bailout. These crises were preceded by a history of similar panics throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Although the United States experienced a host of financial crises, Canada’s financial sector has proven to be far more resilient and stable. Since 1790, the United States suffered 16 banking crises; Canada experienced zero – not even in the Great Depression (Perry). In 2008 and 2009, Canada had no bank failures and no bank bailouts; its recession was far less pronounced than America’s (Bordo 2). Given the safety of Canada’s financial sector, one cannot help but wonder: why is the Canadian banking system so resilient? Canada’s consolidated banking industry, along with its smaller financial markets, allows its financial system to better prevent and weather financial crises. The structure of Canada’s financial sector also encourages its participants to engage in more ethical behavior that reduces the financial system’s exposure to systemic risk.

The Two Banking Systems: An Early History

Since the original founding of the two respective nations, Canada’s banking system has been far more consolidated than its American counterpart. In 1840, over 1,000 small banks existed throughout the United States. By contrast, only 35 active Canadian banks existed in 1868 (Desjardins). The industry-wide consolidation of the Canadian banking system has continued to present day. As of 2018, Canada’s five largest banks– Canada Trust, Royal Bank of Canada, Scotia Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, and Bank of Montreal– hold 89% of the nation’s market share in banking (Desjardins). America’s largest banks hold only 35% of the market share in banking (Desjardins). Throughout the history of these two nations, the Canadian banking system’s more consolidated nature allowed for a greater degree of stability relative to its American counterpart.

Holding all else equal, larger banks are safer and more profitable. Larger banks possess better financial economies of scale. They are better capable of paying for indivisible fixed costs, like loan officers, computer systems, and vault systems than smaller banks. Banks with branches in a variety of different geographical regions can also offer transactional services at lower costs and can more effectively move funds to finance different loan opportunities (Kohn 176). Larger banks are also safer and more profitable. A large, diversified bank with nationwide branches will have a variety of industries to which it can make loans (Kohn 170). Loan defaults resulting from a downturn in one given market will make up a smaller portion of a bank’s overall loan portfolio.

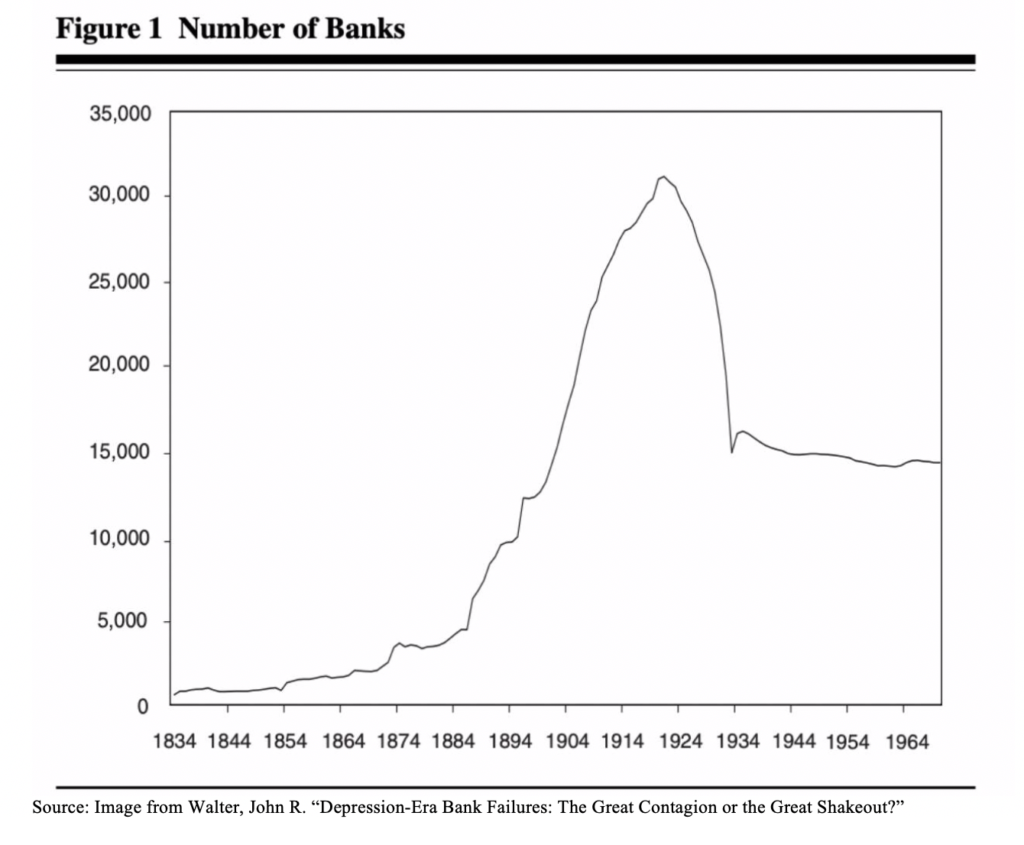

Throughout the early 1800s, banking regulations in the United States prevented the development of these larger, safer institutions. Branch banking– that is, the establishment of multiple branches of one bank– was strictly prohibited (Bordo 6). States were protective of their banks, fearing that a bank with nationwide branches could outcompete their smaller local banks (Bordo, Michael, et al 12). Many political parties also viewed large banks with suspicion (Bordo, Michael, et al 11). The result of these restrictions on branching was the creation of thousands of extremely small banks that only originated loans to local businesses. Figure 1 provides context on the number of US banks during this time period. In certain parts of the country, all of the loans made by a local bank would depend on the value of a single crop; local economic downturns could easily make these institutions insolvent (Bordo 7). The ease with which these country banks could fail was further accentuated by the correspondent banking relationship. To allow its deposits to reach lending opportunities in other geographic regions, many country banks chose to hold deposits at larger regional banks within a given state (Kohn 173). These larger regional banks were often located in regional financial centers that had better access to loan opportunities. Nationsbank of North Carolina, BancOne of Ohio, and Fleet Bank of Rhode Island are some examples of these larger regional banks (Kohn 180). These regional banks would subsequently hold deposits at larger money-center banks, or banks with headquarters in major financial centers like New York.

Although this correspondent banking system allowed the country banks to access loan opportunities in disparate parts of the country, it also proved to be dangerously unstable. The collapse of a regional bank– or even worse, a money center bank– could subsequently cause the collapse of all the banks that had deposited reserves with the institution. It also created inter-bank runs, or situations in which country banks might withdraw deposits from their correspondents, thus causing the failure of the larger money-center banks. An example of this phenomenon was seen during a financial panic in 1873, which began after the failure of Jay Cooke and Company, a private investment bank that had leant heavily to the troubled Northern Pacific Railroad. The failure of Northern Pacific Railroad caused Jay Cooke and Company to fail (Bordo 14).

Just as depositors withdraw their deposits for fear their bank is about to become insolvent, smaller respondent banks chose to withdraw their deposits from money-center banks in New York. Without any deposits to lend out, many manufacturers and railroad companies went into bankruptcy due to a lack of credit from their banks. These bankruptcies caused more money-center banks to fail, thus further accentuating the financial crisis.

Canada, on the other hand, had no such requirements preventing interstate banking. Under the British North American Act that created Canada, the federal government was given exclusive jurisdiction over coinage of currency and banking (Bordo 10). The number of banks was further restricted by a number of barriers to entry. Banks were required to have at least $500,000 in capital (Bordo 11). The ability to freely expand bank branches across Canada, the variety of barriers to entry, as well as the exclusive regulation of banking at the federal level meant the number of Canadian banks were far smaller relative to the United States. In 1874, Canada had 51 banks; by 1925, that number had declined to only 25 (Bordo, Michael D, et al 6). By 1980, Canada’s l1 largest banks had over 7,000 branches across the entirety of Canada. The large size of these institutions, along with their diversified lending, allows them to take full advantage of the aforementioned economies of scale associated with larger banks (Bordo, Michael D, et al 6). Because of this diversification, Canada has never experienced a banking crisis.

The strength of Canada’s banking system can be illustrated by the financial crisis of 1857. The crisis was caused by falling wheat prices around the world, which hit rural wheat-growing communities throughout Canada and the United States especially hard (Fulfer). With less wheat-related freight traffic, many railroad companies also took substantial losses. The result of these economic calamities was a wave of bank insolvencies in rural areas across the country. The catastrophe was exacerbated by the failure of a number of money center banks, like the Bank of Pennsylvania. Respondent banks withdrew deposits from other money center banks, thus causing more bank insolvencies and a wave of bank runs. Between September and October of 1857, American deposits fell from $73.3 million to $63.3 million, creating a liquidity crisis (Fulfer). Although Canada also experienced an economic downturn, its financial system remained stable. Not a single one of its banks failed; no bank runs occurred (Breckenridge 65).

The consolidated nature of Canada’s banks also allows for self-regulation. It is easier to coordinate actions across a small number of businesses than a larger number of businesses. In Canada, self-regulation is conducted through the Canadian Bankers Association, an industry-wide association that represents the banking industry. To ensure depositor confidence in the banking system, members of the Canadian Bankers Association will often join together to guarantee the liabilities of any one of its members if they happen to fail. Such a phenomenon occurred in January 1908, when Sovereign Bank, one of Canada’s large banking institutions, approached insolvency. After suffering substantial losses in the American securities markets, Sovereign Bank quickly neared insolvency, thus causing panic among its depositors. To curb the panic, members of the Canadian Bankers Association assumed Sovereign Bank’s liabilities and branches (Martin 14).

Securities Markets: Canada vs. United States

Thus far, the evidence presented demonstrates that larger and more consolidated banking systems with extensive branching are inherently safer. With interstate branching, the credit risks banks face is more diversified. With more equity, larger banks are able to better withstand losses on their assets. A smaller and more consolidated banking sector also allows for better self-regulation. That being said, the inherent riskiness of the American banking system cannot solely be attributed to its dispersed and unconsolidated nature. It also lies in the fact that the United States has a larger securities market. The presence of these securities markets incentivizes risk-taking among its participants.

As discussed, interstate and intrastate branching was strictly limited in the United States. Besides the correspondent system of banking, another way of moving funds across the country was via financial markets, or markets in which individuals can trade financial instruments that hold monetary value. With a national securities market, a corporation can issue new debt that can be subsequently purchased by investors around the country. The securities market has a long history in America. For example, discount rates on commercial paper, or short-term commercial debt, were quoted in newspapers as early as the 1840s (Bordo 8). The government securities market in the United States also has a long history. A secondary market in government securities has existed since the early 1800s, when Alexander Hamilton issued the first US government securities to fund the Revolutionary War (Kohn 340). Canada’s financial markets, on the other hand, have a more limited history. No discount rates on commercial paper rates were quoted in Canadian newspapers throughout the 19th century (Bordo 8). A secondary market in Canadian government bonds only truly matriculated until the early 20th century (Chen). Because of its interstate banking system, Canada did not need financial markets to move funds across state lines. Although financial markets do exist in Canada today, their size is much smaller relative to their American counterparts.

The close link of financial markets to the American financial system increased its exposure to risk. Securities markets are more difficult to regulate than consolidated banking systems. Securities can be easily moved from region to region or transformed into different financial instruments to evade regulation. Because they can easily be moved off balance sheet, underwriters who securitize loans have less incentive to ensure they make quality loans (Crawford 59). Furthermore, financial markets are susceptible to bubbles. The rising prices of the stock of an exciting new firm can cause investors to recklessly purchase financial assets, resulting in the firm’s value rising beyond its actual value. For example, during the late 1890s, speculation on railroad companies rapidly increased as railroads expanded across the country. Record amounts of capital flowed into equity markets, resulting in the stocks of many railroad companies rapidly rising in value beyond what they were truly worth. As one might expect, the subsequent overexpansion and failure of these firms triggered a major financial panic as investors tried to sell stocks rapidly falling in value.

The Rise of Shadow Banking in the United States

In the United States, subsequent developments would further spawn a new activity called ‘shadow banking’. This activity would expose the American financial to more systemic risks. Shadow banking entails any financial activity conducted beyond the traditional banking system (Chappelow). It is largely unregulated, and encompasses activities ranging from mutual funds to derivatives activities (Chappelow). Shadow banking is massive; the Financial Stability Board found that non-bank financial assets in 2015 amounted to upwards of $92 trillion (Chappelow)[1]. Although systemic risks do originate within this sector, shadow banking is especially important in today’s globalized financial markets. Instruments like asset-backed-securities and commercial paper allow the entire world to participate in finance and provide liquidity to potentially illiquid assets. Derivatives, meanwhile, allow banks to resolve potential maturity mismatches.

Although the history of the individual financial instruments in shadow banking is complex, the overall shadow banking sector originated from the United States during the mid-1970s, when money market mutual funds and repurchase agreements began to move more money into the shadow banking sector (The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report 31) [2].

Money market mutual funds can attribute much of their existence to Regulation Q, which capped interest rates on bank deposits (The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report 29). This regulation allowed mutual funds, or investment companies that pool money to invest in financial instruments, to compete with banks for deposits. After all, mutual funds were not subject to Regulation Q, meaning they were able to pay higher rates than bank deposits (The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report 30). [3] Money market mutual funds proved to be immensely popular. As stated in the Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, assets in these mutual funds jumped from 3 billion dollars in 1977 to 1.8 trillion dollars by 2000. To earn even higher returns, investors might choose to put their money in exchange traded funds or hedge funds. Repos, or repurchase agreements, also began to proliferate in the 1970s (The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report 31). In a repurchase agreement, financial institution A will lend treasury bonds to financial institution B in return for cash roughly equivalent to the value of the treasury bonds (Reiff). The cash proceeds can be used by financial institution A to engage in activities in the shadow banking sector, like taking positions in derivatives. After a short period of time, this transaction reverses. The original sum of money financial institution A had loaned from B is returned to B; institution A then receives its securities it had loaned to B.

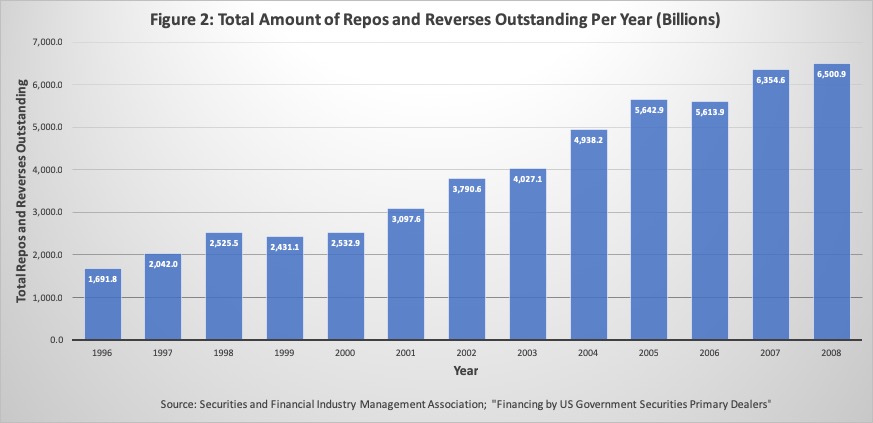

Repurchase agreements are essentially collateralized loans. Banks and other institutions can use these transactions to quickly raise liquid cash to engage in riskier activities on the shadow banking market, like taking positions in derivatives. Figure 2 provides context on the total sum of these transactions. With money market mutual funds and repurchase agreements, substantial amounts of money moved from the traditional banking sector into the shadow banking sector, an area of banking far less regulated. The disintermediation of money from traditional banking to the shadow banking would also allow for the expansion of institutions like securities firms and hedge funds, who can take positions on instruments in the shadow-banking sector.

Although Canada also has a substantial shadow banking sector, its relative size is far smaller than its American counterpart. It is estimated that America’s shadow banking sector is 1.5 times the size of its GDP (Cox)[4]. By contrast, the Bank of Canada estimates the shadow banking sector is approximately half the size of Canada’s GDP (Last)[5]. Unlike the United States, Canada never had substantial restrictions on interest rates paid to deposits, meaning that the disintermediation of money from traditional banking to shadow banking was less prevalent. The limited nature of asset securitization in Canada also meant that activities that moved money from regulated to unregulated sectors via repurchase agreements was far more limited. After all, conducting a repurchase agreement inherently requires the existence of securities that can be loaned in return for liquid cash.

Mortgage Finance: A Case Study

A number of scholars, particularly Michael Bordo, Angela Redish, and Hugh Rockoff in their paper “Why Didn’t Canada Have a Banking Crisis in 2008 (or in 1930, or 1970, or…)?”, have used the history of mortgage finance in the United States and Canada to exemplify many of the aforementioned points about banking safety and regulation. This paper further expands upon these analyses.

Prior to the Great Depression, mortgage finance in America was heavily localized and decentralized due to branching restrictions (Kohn 377). Funds were raised locally; mortgage banks were further limited by regulations restricting lending to within 50 miles of the lending institution (Kohn 377). These restrictions meant that the mortgage market varied considerably from location to location. In the Sun Belt, where the housing market was booming, mortgage financing would be scarce; in the Rust Belt, where the housing market was in a slump, mortgages would be plentiful (Kohn 377). This fractured mortgage market nearly collapsed during the Great Depression. To resurrect the mortgage market, the federal government began efforts to create a secondary market in mortgages. The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mac) were created with this intention (Kohn 382). The FHA provided mortgage insurance and a standard mortgage contract to certain categories of borrowers; Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchased existing mortgages and securitized them (Nielsen). Today, Fannie and Freddie securitize the overwhelming majority of all mortgages, which includes both non-FHA insured, FHA-insured, and uninsured mortgages (Kohn 391).

As discussed, Canada’s financial institutions were never subject to geographical branching restrictions, thus allowing them to access the national capital market. This fact meant that securitization was less necessary. Such a fact is reflected through the extent of mortgage securitization in Canada: before 2000, less than 10% of all residential mortgages were securitized (Bordo 28)[6]. In the United States, approximately 60% of all residential mortgages are securitized (Crawford 58). Securitization poses a number of moral hazards. One can easily trade away a security, meaning there are lower incentives to have high underwriting standards for the underlying loans (Crawford 59). If the loans default, the losses will be another institution’s losses. The structure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also contributed to their exposures to risk. Until 2008, the two institutions were government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), meaning they are private corporations with public aims. Their returns are all given to the private sector Therefore, they have an incentive to increase profits by engaging in riskier activities like subprime lending (Crawford 58).

Unlike its American counterpart, mortgage securitization in Canada is largely conducted by a government-owned company called the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Its ownership by the Canadian government means it operates with stricter supervision. Mortgages securitized by the CMHC are all insured by the agency. Thus, the lender will be paid a portion of the principal of the loan in the event that a mortgage forecloses (Crawford 57). CMHC has an incentive to securitize prime mortgages to reduce the likelihood of an insurance payout.

As is widely known, collateralized debt obligations (CDO) magnified the financial crisis after the American mortgage bubble popped (“Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO)”). A collateralized debt obligation is a type of derivative that pays investors out of a pool of revenue-generating sources (“Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO)”). It is often divided into multiple tranches, each with varying levels of risk. Using financial engineering, cash flows from these assets can be distributed to different investors depending on their exposure to risk within the CDO (“Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO)”). Unfortunately, when the mortgage-backed-securities within the CDOs failed, these derivatives spread the resulting losses to the wider financial sector. Institutions that may have had shares of the CDO but might not have actually owned mortgage-backed-securities took losses.

A CDO’s very existence requires two things less prevalent in Canada– a strong securities market and a large shadow banking sector. A CDO is essentially a pool of securities that offers returns. Without a substantial amount of securitization, this instrument simply cannot exist. A CDO is also created in the Over-The-Counter (OTC) Market, an unregulated derivatives exchange (Kohn 496). This market allows its customers to tailor derivatives to the unique demands of its participants, something that is also needed for a CDO. The disintermediation that allowed for the rise of the shadow banking sector did not occur as extensively in Canada as its American counterpart. The result of these two factors meant that collateralized debt obligations were less prevalent in Canada, thus reducing the extent to which financial contagion spread throughout its economy.

Ethics: Canada vs. United States

The structure of the Canadian and American financial systems also creates different ethical incentives for its participants. ‘Ethical behavior’ here describes behavior that minimizes the financial system’s overall exposure to risk without compromising its efficiency. Canada’s financial system is more likely to promote ethical behavior among its participants. The Canadian banking sector is also more capable than its American counterpart at preventing the development of systemic risks. Its financial sector maintains a high level of competition, though it trails its American counterpart in innovativeness.

In Canada, the financial sector is largely regulated by one central agency– the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) (Bordo, Michael D, et. al)[7]. This agency supervises institutions like commercial banks, insurance companies, trust funds, and pension funds. Banks can only be chartered by the federal government. The United States, on the other hand, features a series of overlapping regulators. There are two basic categories of banks: banks with a national charter and banks chartered by states. States are notorious for having looser oversight over banks. Banks are regulated by a series of agencies, including the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (Schmidt). Insurance companies are all regulated by states; no single body regulates pension funds or trust funds, while securities markets are jointly regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) (Schmidt). The patchwork of regulators at the state and federal level can create a ‘race to the bottom’, or competition between regulators to lower regulatory standard standards for banks.

The more banks chartered by a given agency, the more fees agency receives. When a bank changes its charter, the budget of the agency that originally chartered the bank can decrease. For example, when Chase Bank changed from a federal to state charter in 1995, the combined fees lost to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) equaled 2% of its entire budget (Kohn 597). As a result, regulators can be incentivized to relax regulation in an attempt to have more banks chartered by a given agency, thus creating a ‘race to the bottom’– a race to loosen regulation. Such a phenomenon can be illustrated after the passage of Dodd-Frank, the post-2008 financial reform bill. After Dodd-Frank consolidated the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) with the OCC, many thrifts changed from national charters to state charters (Silver-Greenberg). Compared to federal regulators, state regulators tend to have looser oversight standards (Silver-Greenberg).

Although the ‘race to the bottom’ can cause regulators to sacrifice the public good for the sake of more business, this competition also encourages agencies to more carefully examine new financial products. Without competition, regulators could be tempted to be more conservative with approval of new products (Kohn 597). After all, new products create new risks. However, with regulatory competition, a nationally chartered bank can always switch to a state charter to win approval for a new product. Because state-chartered banks have lower regulatory standards, state regulators have led the way in approving new innovations. For example, Massachusetts state thrift regulators were the first to allow negotiable accounts (Kohn 597). State regulators also led the way to approving branch banking (Kohn 597). To avoid the loss of business, federal regulators must adopt laxer standards for the approval of new products (Kohn 597).

Because bank charters are only granted by the federal government, Canada does not face the issue of regulatory competition. Federal regulators can impose tighter restrictions on banks and financial products without fear of competition. The structure of financial regulation in the United States, on the other hand, is more business-friendly. If one regulator is too strict, a bank can always shop for a looser regulator. As a result, new financial instruments are more likely to gain approval in the US than in Canada. Indeed, many financial innovations originate from the US. Instruments like derivatives and money market mutual funds all have American histories. This fact obviously poses a number of ethical complications. On one hand, these instruments meet a variety of financing needs in the economy; on the other hand, they create new and unpredictable risks.

In both Canada and the United States, the financial sector is very competitive. With the elimination of interstate branching restrictions, American banks face competition for loan opportunities both nationally and globally. The existence of well-developed securities markets and a large shadow banking sector in America also means that commercial banks face competition from investment companies like money market mutual funds and foreign banks for deposits. As this paper has discussed, this competition can also promote speculation and moral hazard. With an extensive securities market, banks can easily remove a bad loan from its balance sheet; when profits are difficult, banks may choose to increase their leverage (Kohn 602)[8].

The Canadian financial system is also competitive. The empirical standard for this evaluation is the Panzer-Rosse statistic, also known as an H-statistic (Allen 40). H-values greater than 0 indicate the existence of competition; values less than 0 indicate the existence of oligopolies or monopolies (Allen 40). Empirical studies on Canada’s banking system have generally reported H-statistics greater than 0, indicating that the sector is competitive (Allen 42). Such a statement might seem surprising: with five major banks dominating the banking system, this sector appears to be an oligopoly. Although its banking system is highly concentrated, substantial competition exists between banks and non-bank intermediaries like credit unions (Allen 39). Credit unions are nonprofit organizations that offer many of the same services as a bank (Green). These organizations are very popular, with over five million Canadians claiming membership to the nation’s 252 credit unions (“Who Are Canada’s Credit Unions”).

Both the Canadian and American banking systems are competitive. With competition from overseas and nonbank intermediaries, there is no space for inefficiency. However, Canada’s regulatory regime is more likely than its American counterpart to promote ethical behavior among its regulators. With regulation consolidated in one agency, a ‘race to the bottom’ is less likely to occur. That being said, this consolidation has impacts on the development of new financial instruments, as banks cannot shop for looser regulators.

Conclusion

This paper has cited a variety of factors contributing to the resiliency of the Canadian banking system. With extensive interstate branching, Canada’s banks were able to better weather regional crises. A lower level of securitization reduced the financial sector’s exposure to risk. Incentives to develop an unregulated shadow banking sector, such as caps on interest rates for bank deposits, were also less present. Canada’s regulatory regime is also more effective at preventing the development of systemic risks. Although its banking system is heavily consolidated, it is still competitive. Canada’s financial sector offers the United States a number of lessons from which its southern neighbor can learn.

Endnotes

[1] Due to the unregulated nature of shadow banking, estimates regarding its size vary.

[2] A money market mutual fund is a mutual fund that invests in safe debt instruments like highly rated commercial paper and treasury bonds.

[4] Estimates vary due to the unregulated nature of shadow banking.

[5] Estimates vary due to the unregulated nature of shadow banking.

[6] Under the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program, implemented in 2009, mortgage securitization in Canada has risen to 35% of all residential mortgages (Crawford 58).

[7] Securities dealers and brokers, investment companies, and credit unions are only regulated by provincial governments (“LibGuides: Global Financial Regulation: Canadian Financial Regulators”)

[8] Leverage is the use of debt rather than equity to purchase new assets, like underwriting new loans. Leverage can magnify the profits or losses of a bank.

Bibliography

Allen, Jason, and Walter Engert. “Efficiency and Competition in Canadian Banking.” Bank of Canada Review, 2007, pp. 33–45.

Amadeo, Kimberly. “How Congress Created the Greatest Bank Collapse Since the Depression.” The Balance, The Balance, 25 June 2019, www.thebalance.com/savings-and-loans-crisis-causes-cost-3306035.

Bordo, Michael D, et al. “A Comparison of the United States and Canadian Banking Systems in the Twentieth Century: Stability vs. Efficiency?” NBER, NBER Working Paper Series, 1 Nov. 1993, www.nber.org/papers/w4546.

Bordo, Michael D, et al. “WHY DIDN’T CANADA HAVE A BANKING CRISIS IN 2008 (OR IN 1930, OR 1907, OR …)?” National Bureau of Economics Research, Aug. 2011, www.nber.org/papers/w17312.pdf.

Breckenridge, R. M. The History of Banking in Canada. U.S. G.P.O., 1911.

Chappelow, Jim. “Shadow Banking System Definition.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 15 May 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/s/shadow-banking-system.asp.

Chen, James. “Canada Savings Bond (CSB).” Investopedia, Investopedia, 12 Mar. 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/c/csb.asp.

Chen, James. “Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO).” Investopedia, Investopedia, 17 May 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cdo.asp.

Cox, Jeff. “Shadow Banking Is Now a $52 Trillion Industry, Posing a Big Risk to the Financial System.” CNBC, CNBC, 11 Apr. 2019, www.cnbc.com/2019/04/11/shadow-banking-is-now-a-52-trillion-industry-and-posing-risks.html.

Crawford, Allan, et al. “The Residential Mortgage Market in Canada: A Primer.” Financial System Re, Dec. 2013, pp. 53–63.

Desjardins, Jeff. “A Tale of Two Banking Sectors: Canada vs. U.S.” Visual Capitalist, 12 Mar. 2019, www.visualcapitalist.com/canada-u-s-banking-differences/

Fulfer, Johnny. “Financial Instability and the Panic of 1857.” The Economic Historian, 6 July 2018, www.economic-historian.com/2018/07/financial-instability-and-the-panic-of-1857/.

Green, Mitchell Grant and Laura. “Credit Union Definition.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 25 June 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/c/creditunion.asp.

Last, Kaitlin. “Canada’s $1.1 Trillion Shadow Banking Sector Is Now Half As Large As Banks.” Better Dwelling, 20 Apr. 2017, betterdwelling.com/canadas-1-1-trillion-shadow-banking-sector-now-half-large-banks/.

“LibGuides: Global Financial Regulation: Canadian Financial Regulators.” Canadian Financial Regulators – Global Financial Regulation – LibGuides at Ontario Securities Commission, Ontario Securities Commission, research.osc.gov.on.ca/globalreg/cdnreg.

Martin, Joe. “The Forgotten Credit Crisis of 1907.” Rotman School of Management- University of Toronto. www.rotman.utoronto.ca/-/…/Forgotten_Credit_Crisis_of_1907_10-29-14.pdf?…

Nielsen, Barry. “Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the 2008 Credit Crisis.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 1 July 2019, www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/fannie-mae-freddie-mac-credit-crisis.asp.

Perry, Mark J. “Why the US Banking System Is so Dysfunctional vs. Canada’s.” American Enterprise Institute, 10 Apr. 2013, www.aei.org/publication/why-the-us-banking-system-is-so-dysfunctional-vs-canadas/.

Reiff, Nathan. “Repurchase Agreement (Repo).” Investopedia, Investopedia, 15 July 2019, www.investopedia.com/terms/r/repurchaseagreement.asp.

Schmidt, Michael. “Financial Regulators: Who They Are and What They Do.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 25 June 2019, www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/09/financial-regulatory-body.asp.

Securities and Financial Industry Management Association; “Financing by US Government Securities Primary Dealers” https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/funding-us-repo-sifma.xls

Silver-Greenberg, Jessica. “Small Banks Shift Charters to Avoid U.S. as Regulator.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 3 Apr. 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/business/small-banks-shift-charters-to-avoid-us-as-regulator.html.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States. Washington, DC: Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, 2011. Print.

Walter, John R. “Depression-Era Bank Failures: The Great Contagion or the Great Shakeout?” SSRN, 6 Dec. 2012, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2185582.

“Who Are Canada’s Credit Unions.” Credit Unions in Canada, Canadian Credit Union Association, www.ccua.com/credit_unions_in_canada.