Green Bonds Without Greenwashing

By Thomas G. Walton

This post is dedicated to Steve Hoey (1962-2022)

Global leaders must act together in establishing universal regulations to govern the green bond market if green bonds are to be used efficiently in the fight against climate change. The profound gravity of this threat merits a true global response. As such, the ethical responsibility of the financial sector to act against climate change has grown apparent in recent years.

Climate Finance (or “CliFin”) refers to any financial service, instrument, vehicle, or regulation designed to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change. One example of CliFin is the green bond. A green bond is similar to a regular bond in that it provides its issuer with funding through the same mechanism; however, a green bond differs from a regular bond in that any funds generated through green bonds are specifically earmarked for projects aiming to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change. Thus, the purpose of green bonds is to provide investors with an easy and low-risk means to invest in an environmentally conscious way.

Unfortunately, practical limitations have decreased the effectiveness of green bonds in the fight against climate change. A lack of global standardization in definitions and measurements has led to some issuers of green bonds “greenwashing.” Greenwashing, in this context, is when an issuer of a green bond exaggerates the positive environmental impact of a project in an effort to secure funding from environmentally conscious investors. Greenwashing is at best misleading if not outright dishonest; and yet, the practice is difficult to prevent as there is no international regulation to determine what qualifies as a green bond. For investors, greenwashing decreases trust in the green bond market, and thus acts as a disincentive to buy green bonds. This, in turn, negatively impacts sale of green bonds not greenwashed. With global cooperation the necessary regulations could be introduced to eliminate greenwashing and amplify trust in the green bond market. Green bonds are a good first step towards facilitating environmentally conscious investing, but in order to encourage more people to invest in green bonds it is essential an international organization clearly define and enforce eligibility criteria for projects funded by green bonds and thereby avoid the problem of greenwashing.

A Brief History of Green Bonds

Money secured by green bonds is meant to fund projects aiming to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change. The World Bank claims credit for issuing the first green bond in November 2008 in response to a group of Swedish pension funds looking to invest in projects that would help mitigate climate change.[1] The European Investment Bank, however, issued its Climate Awareness Bond (CAB) first, in 2007.[2] Shortly after, other multilateral development banks (MDBs) helped expand the market for green bonds. For several years the market was dominated by MDBs, until 2013 when green bonds issued by corporate issuers and government-backed entities saturated the market.[3] As the number and types of issuers expanded, so did the variety of projects funded by green bonds. Where MDBs had predominantly focused on green infrastructure, new issuers sought funding for energy, climate change adaptation, water, waste, buildings, and transport. This transition saw the green bond market grow from $1.5 billion in 2007 to $389 billion in 2018.[4] The massive expansion in the market for green bonds, a cause for optimism, demonstrates investor desire to stall climate change. Still, some issuers have been exploiting this relatively new market’s lack of regulation by “greenwashing” projects to secure more funding.

Defining “Green”

The problem of greenwashing comes down in the main to a singular issue: definitions. Words like “green” and “sustainable” have become a rallying cry for climate activists. Though such words have gained popularity and helped raise awareness of climate change, their lack of specificity may be harming the movement. The general sentiment of concepts like “green” and “sustainable” places importance on the environment while still encouraging development and advocating for equity. Disagreements arise when examining the tradeoffs of linking environment, development, and equity. Even the UN definition of sustainability, “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” seems disappointingly vague.[5] Because of these indistinct definitions, different countries have varying criteria to qualify for “green” labels. Consequently, international investors have an especially hard time navigating the green bond market.

This lack of clear definitions results in confusion and errors when it comes to policy. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, first highlighted the importance of universal definitions and measurements for easily interpretable sustainability indices.[6] Since then, over 500 sustainability indices have emerged, evaluating countries on three dimensions: economic, environmental, and social conditions. In their analysis of 11 well respected indices, Böhringer and Jochem observe that despite the indices’ best efforts to be concise and transparent, they fail to meet fundamental scientific requirements.[7] Because of the ambiguity in definition, measurements across countries are simply too varied to make any sort of meaningful comparison.

In the same way, some issuers of green bonds take advantage of the ambiguity of the word “green.” Since there is no law governing what can be called green, some issuers exaggerate any possible aspect of a project that could be interpreted as green. Repsol’s issuance of green bonds is one notable example of this kind of greenwashing . In 2017 Repsol issued the first green bond by an oil and gas company, claiming the funds would help them operate more efficiently, and thereby help reduce its carbon footprint.[8] Clearly, funding an oil company is not what most investors have in mind when purchasing a green bond. Yet, Repsol was able to use the lack of definition and regulation on what constitutes “green” to its advantage.

Issuers of Green Bonds

According to an Institute for Climate Economics 2016 report, there are seven types of green bonds: 1) Corporate bonds backed by a corporation’s balance sheet, 2) Project bonds backed by a single or multiple projects, 3) Asset-backed securities (ABS) or bonds collateralized by a group of projects, 4) Covered bonds with a recourse to both the issuer

and a pool of underlying assets, 5) Supranational, sub-sovereign and agency (SSA) bonds issued by IFIs and various development agencies, 6) Municipal bonds issued by municipal governments, regions, or cities, and 7) Financial sector bonds issued by an institution to finance on-balance sheet lending.[9] In this section, we will examine differences in green label standards for bonds issued by the World Bank, in the EU, and in China. The World Bank issues SSA bonds and follows voluntary guidelines to please investors. Within the EU each country has its own regulations for the various types of bonds, though investors have incentivized issuers to be especially transparent regardless of regulations. China has four different bodies each responsible for regulating different types of bonds, allowing for more cases of greenwashing than within the EU.

Green Bonds Issued by the World Bank

SSA bonds are worth talking about for two reasons. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, IFIs and MDBs were the first institutions to issue green bonds, thus spurring this now massive market. Secondly, as such institutions do not pursue the goal of profit maximization, more emphasis is placed on a project’s environmental effects. For example, the World Bank’s criteria for project selection was praised in an independent review by the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research at the University of Oslo (CICERO) as being a sound basis for selecting climate-friendly projects.[10] CICERO describes the World Bank’s project selection process in the following way. Eligible projects include those that mitigate effects of climate change, such as investments in low-carbon and renewable energy. Secondly, eligible projects include those that target the adaptation to climate change, often infrastructure, or climate-resilient growth projects. Importantly, no fossil fuel power generating projects are eligible for funding from World Bank issued green bonds. Experts in fields such as energy, climate change, transport and environment are responsible for selecting eligible projects. Finally, once a project has been approved, there are robust systems in place to monitor and report on the progress of the project.[11] For example, impact reporting is in effect an investor newsletter listing relevant statistics and results so details of the project’s environmental impact are more readily available to the investor.

Impact reporting in particular, while incurring an extra cost on the issuer of the bond, provides investors with an extra incentive to invest as they can read about the positive effects of their investments. Recognizing the importance of impact reporting, the World Bank (along with several other IFIs and MDBs) has collaborated with the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) in an effort to create a harmonized framework for impact reporting.[12] ICMA published up to date guidelines (https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2021-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2021-140621.pdf) in June 2021 (dubbed the Green Bond Principles or GBP), placing an important role on transparency and disclosure in an effort to increase the perceived integrity of the green bond market.[13]

ICMA’s GBP are made up of four core components along with two key recommendations for heightened transparency. The four core components are: 1) Use of proceeds, 2) Process for evaluation and selection, 3) Management of proceeds, and 4) Reporting. The two key recommendations are: 1) Green bonds frameworks, and 2) External reviews. Within the use of proceeds documentation an issuer must describe both what eligible green projects will be funded, and how such projects will be funded through the proceeds of their green bond. ICMA lists ten categories of eligible projects, ranging from renewable energy to clean transportation. Next, the issuer must provide a document explaining the environmental sustainability objectives of the eligible green project(s) and how they align with their respective eligible project category. Under the management of proceeds requirement, the issuer is encouraged to provide investors with regular updates about the whereabouts of the net proceeds raised by the bond throughout the duration of the project. Finally, the issuer should make annual reports regarding the use of proceeds to keep investors informed.[14]

If issuers would like to demonstrate to their investors a heightened commitment to transparency, they can follow the key recommendations as well. Firstly, by publishing a green bond framework the issuer can summarize how its green bond aligns with the five high level environmental objectives of the GBP (climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, natural resource conservation, biodiversity conservation, and pollution prevention and control). Lastly, issuers are encouraged to appoint an independent external review provider to provide investors with an unbiased assessment of the integrity of their green bond.[15] ICMA’s work on GBP is a good first step towards ensuring trust in green bonds, although the guidelines are completely voluntary and unenforceable. The voluntary nature of such guidelines allows greenwashers to be intentionally vague or misleading.

EU Standards and Norms

Currently, there is no legally binding European consensus on green label standards, rather each country is responsible for setting national regulations. While the EU Green Bond Standard (EU GBS) has yet to be adopted into law, European investors have demonstrated their collective power in minimizing greenwashing within the EU by incentivizing issuers to value transparency and disclosure. Furthermore, their collective action has indirectly prompted the European Commission to pursue legislation adopting an EU GBS.

After Repsol issued its green bond in 2017, the controversy quickly turned to outrage amongst investors. As European investors made their dissatisfaction heard, a dialogue between issuers and investors sparked a change in mindset. It became clear to European issuers that if their green bonds were to be successful within the EU, they would have to publicly signal their plans to initiate and accelerate sustainable business models. According to a special feature in a Bank for International Settlements (BIS) quarterly review, for some corporate issuers this new approach has even resulted in better pricing and lower market execution risk compared to traditional bonds.[16]

Upon realizing the benefits of such transparency and disclosure for both investors and issuers, the Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on sustainable finance recommended establishing an EU GBS in a report released in January 2018.[17] “Creating an EU Green Bond Standard and labels for green financial products” was then included as an action in the 2018 Commission action plan on financing sustainable growth.[18] On June 18th, 2019, the Commission’s Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG) published its assessment of an EU GBS. The report proposed that the Commission creates a voluntary EU GBS to strengthen effectiveness, transparency, comparability, and credibility of the green bond market.[19] The TEG’s final report built on its interim report (published March 6th, 2019) after receiving feedback from more than 100 organizations.[20] Recognizing the importance of such standards, a large majority of participating stakeholders supported the creation of a voluntary EU GBS. This prompted the TEG to give usability guidance and an updated proposal for an EU GBS in its March 2020 report. The report acts as a guide to issuers for the proposed EU GBS and the set-up of a market based registration scheme for external verifiers. It also contains some updates on the proposed standards.[21]

The actual document contains 51 pages of explanations, definitions, regulations, and implementation guidance influenced by ICMA’s GBP. The TEG’s proposed model is made up of four core components: 1) The alignment of the use-of-proceeds with the EU Taxonomy; 2) The content of a green bond framework to be produced by the issuer; 3) The required allocation and impact reporting; and 4) The requirements for external verification by an approved verifier. Thus, for an issuer to receive a green label the issuer must firstly publish a green bond framework at or before the time of issuance. The framework must clearly describe (i) the issuer’s green bond strategy and alignment with the EU taxonomy; (ii) the types of green project categories to be financed; and (iii) the methodology and process regarding allocation and impact reporting. Secondly, the issuer must produce annual allocation reports and at least one impact report throughout the allocation of funds. The annual allocation reports must include (i) a confirmation of alignment with EU GBS; (ii) a breakdown of allocated amounts per project or portfolio; and (iii) a geographical distribution of projects. Finally, an external verifier (as defined by the TEG) must approve the green bond framework, the final allocation report, and the impact report published by the issuer. If all steps are followed successfully, the issuer—whether located inside or outside the EU—will receive a green label for their bond.[22]

In response to the TEG’s work, the Commission launched two parallel consultations exploring the possibility of a legislative initiative for an EU GBS. Firstly, the public consultation on the renewed sustainable finance strategy (running from 6 April 2020 – 15 July 2020) aimed to collect the views and opinions of interested parties as to inform the Commission’s renewed strategy on sustainable finance.[23] More importantly, the targeted consultation on the EU GBS (running from 12 June 2020 – 2 October 2020) aimed to determine the nature of the EU GBS’s legal form.[24] As a result of these consultations, President von der Leyen announced the establishment of an EU GBS as a key new initiative for 2021 in her State of the Union 2020 speech. In the same speech she announced that the Commission will set a target for 30% of the Next Generation EU fund’s 750 billion euros to be raised through green bonds.[25] Just over a month later, the Commission published the Commission Work Programme 2021, scheduling the legislative proposal for an EU GBS to be delivered in the second quarter of 2021.[26]

Since the Repsol scandal in 2017 there have been few cases of greenwashing as controversial within the EU. Investors’ close monitoring of the market in Europe has caused issuers to voluntarily emphasize transparency and disclosure. In fact, a Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) report on the green bond market in Europe in 2018 asserts that over 98% of green bonds issuance in Europe receives at least one review from independent institutions such as Vigeo Eiris or CICERO.[27] Despite this oversight, there are still the occasional cries from investors alleging greenwashing within the EU. For example, in 2019 a representative of Nuveen, an American asset manager, accused Italian electricity giant Enel of greenwashing their green bonds. The allegation claimed Enel’s green bond was linked to a commitment to increase the coupon by 25 basis points if the company failed to meet its renewables capacity development targets by the end of 2021.[28] Enel has publicly provided green bond reports for 2017, 2018, and 2019, while also providing several investor presentations.[29] Upon independently reviewing Enel’s green bonds in October 2020, Vigeo Eiris asserts that Enel’s green bonds are in line with ICMA’s Green Bond Principles detailed in June 2020.[30] The issue comes down to definitions. What Nuveen considers greenwashing is viewed as acceptable by Vigeo Eiris and ICMA, once again highlighting the need for effective legislative standardization.

The Problem with China’s Green Bond Standards

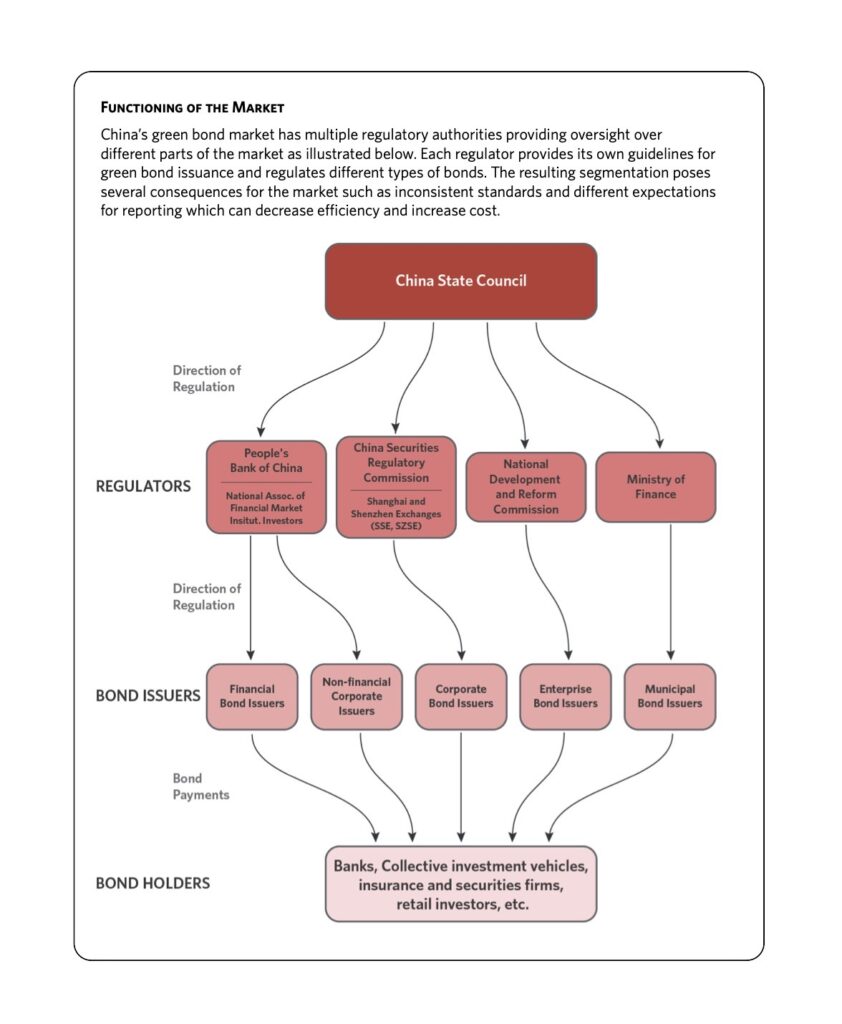

Greenwashing in China is of greater concern. While China has the world’s second largest and fastest growing green bond market, it is also particularly infamous for greenwashing. The People’s Bank of China, the China Securities Regulatory Commission, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the Ministry of Finance each have their own eligibility criteria for green bonds, and are in charge of regulating a separate portion of the market.[31] Figure 1 illustrates China’s method of regulation concerning green bonds.[32] These separate taxonomies establishing eligibility criteria for green bonds in China have done little more than cause confusion, especially for foreign investors.

Chinese regulations could be more effective at preventing greenwashing. Where the EU advocates climate change mitigation and adaptation, a 2019 Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) report states that Chinese standards generally highlight the importance of pollution reduction, greenhouse gas reduction, resource conservation and ecological protection.[33] At first glance these seem like a fine set of criteria, but there are loopholes that allow for greenwashing. The criterion for pollution reduction is especially harmful, as it technically qualifies projects increasing the efficiency of coal or fossil fuel plants as “green.”[34] Furthermore, S&P Global Ratings analysts Yamaguchi and Ahmad, point out that Chinese rules allow for up to 50% of green bond proceeds to pay back bank loans or fund general working capital instead of funding a specific project (the CBI standard is 5%).[35] Another cause for concern is the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE). According to a 2019 CBI report, the SSE allows corporations to issue green bonds on the SSE’s platform without even having to specify the project so long as over 50% of a corporation’s operating revenue is generated in a defined “green” sector and at least 70% of the raised funds are used in green sectors.[36] While these regulations certainly seem alarming, the same CBI report says these regulations may not be always so bad.

According to the report, China issued $55.8bn in green bonds on both the domestic and overseas markets in 2019. Of that $55.8bn, CBI determined $24.5bn (or 43.9% of bonds issued in 2019) in some way violated their criteria for being given a “green” label and were thus excluded from CBI’s internationally aligned green bond database. Upon a more detailed investigation CBI found at least $12.4bn of the $24.5bn were actually allocated to green projects that aligned with CBI’s values. An example of green bonds that had to be excluded for technical reasons are two bonds issued by Beijing Enterprises Clean Energy Group Limited (BECEGL), a company that gets 99% of its revenue from solar and wind energy.[37] Because two of its labeled greenhouse bonds use 27% and 30% of proceeds respectively for general corporate purpose (larger than CBI’s allowance of 5%) the bonds could not be included in CBI’s internationally aligned green bond database.[38] As a renewable energy company, BECEGL is the sort of company an environmentally conscious investor would want to support. Yet because of its own criteria, CBI cannot grant BECEGL bonds a green label. When you adjust for cases like these, a more accurate estimate of newly-issued greenwashed green bonds in China in 2019 is $12.1bn (or 21.7%). This number is still relatively high, but the drop from 43.9% shows that China’s greenwashing problem might be exaggerated by confusing regulations and poor transparency. Relaxed standards combined with a lack of voluntary transparency risk alienating foreign investors from green bonds issued in China.

Green Bond Investors

Adam Smith, often dubbed the father of economics and capitalism, argues that individuals should act in their own rational self-interest. This mindset has become engrained in our financial system. We often see profit maximization prioritized over other important objectives, such as sustainable development. To be useful in the fight against climate change, this mindset of the financial sector will have to change. Individual investors should consider the environmental impacts of their investments. This is not a political issue, but rather an ethical one.

From a utilitarian perspective, investors have an ethical responsibility to invest in an environmentally conscious way. When faced with an investment choice, an investor should choose the option that will produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Thus, when deciding whether to prioritize profit maximization or environmental benefits, investors should consider the environmental externalities their investment decisions will impose on future generations. Different ideologies ranging along the spectrum from the economic left to right will disagree to what extent utilitarian principles should influence investors’ decisions. Still, most would agree that if an investor has the financial means to invest in an environmentally conscious way without any major sacrifice on returns, then they should do so from an ethical standpoint. The idea behind the green bond is to provide investors with a relatively simple means to do so.

The two main disincentives to purchasing green bonds are greenwashing and currency exchange rate volatility. Some argue the returns on green bonds should be lower than for traditional bonds due to the increased cost to the issuer of a green bond brought on by impact reports as well as a willingness of investors to trade off at least some returns for the “feel-good” premium of environmental benefits. In practice, returns on green bonds do not seem to differ significantly from their traditional counterparts.[39]

Greenwashing provides the biggest disincentive to investors considering green bonds. Some investors simply do not have time to do the necessary due diligence when figuring out what sort of project they would like to help fund. The idea they may be funding a coal plant could be enough to dissuade an investor from buying any green bond.

Exchange rate volatility—particularly in emerging economies—can influence an investor’s decision to purchase green bonds. By the time the investor receives returns the exchange rate between the investor’s domestic currency and the foreign currency used to pay for the bond might have depreciated to a level where the investor makes no real gain (or even incurs a loss) after exchanging back to the domestic currency.

Despite these hurdles there is cause for optimism as investors seem eager to buy green bonds. In fact, a CBI report covering 46 EUR and USD green bonds during the first two quarters of 2020 notes the average oversubscription for green bonds was 2.6x compared to 2.3x for a selection of traditional bonds.[40] While EUR and USD green bonds are less likely to be greenwashed, this report demonstrates the demand for green bonds is already high and seems to be growing.

Policy Implications and Challenges

Solving the problem of greenwashing will require a coordinated effort from all actors involved in the green bond market, including issuers, investors, independent rating agencies, and governments.

Because of the distrust in the green bond market brought on by greenwashing, issuers of green bonds have a duty to distinguish themselves from potential greenwashers by means of transparency and disclosure. Impact reporting seems to be an effective way of communicating environmental impacts of projects to investors. Perhaps the reason some companies are not as transparent as others is that impact reporting incurs an additional cost on the issuer. To alleviate this burden, issuers should advocate for preferential treatment from governments in the form of tax cuts or subsidies as an incentive to provide quality impact reports.

Next, investors, like everyone else, have a responsibility to fight climate change. There is a good case to be made that investors have the ethical responsibility to invest green, thereby doing something good for the vast number of people who will have to live with the effects of climate change. Implicitly, this means investors also have the responsibility to educate themselves to avoid the purchase of greenwashed bonds. Otherwise, there is little that investors can do on an individual level. Collectively, on the other hand, investors can continue applying pressure on other actors in the market to do everything they can to ensure confidence in the market.

Independent institutions such as CBI or CICERO have important roles to play in the fight against greenwashing. Providing guidelines to issuers as to how to qualify for a green label is only one step. Independent rating agencies should work together to form a universal set of rules. More easily said than done, collaboration on an international scale would be a good first step towards this goal. Any guidelines should be wary of being too limiting as to avoid excluding reasonable green bonds from attaining a green label (as we observed with BECEGL in China). Instead, there should be a greater emphasis on transparency and disclosure. Ideally, judgements could be made on an individual basis, with a published report detailing why a bond did or did not qualify for a green label. In practice, however, this process requires a lot of resources. Finally, independent rating agencies are useful to investors, but do not carry any legal power. Thus, such agencies should continue to advocate for an international organization to regulate the green bond market.

Governments have two main responsibilities in eliminating greenwashing. Firstly, governments will have to collaborate to establish an international body to regulate the market for green bonds. A single universal standard of a green bond label should reduce investor confusion and mistrust. Governments could consult with independent rating agencies when developing those standards. Secondly, governments should work to incentivize both issuing and buying green bonds. Whether through tax cuts or subsidies, governments should explore a variety of incentives.

If all actors involved do their part, integrity can be restored to the green bond market, allowing the market to continue expanding and for society to reap more of the benefits of green bonds.

Societal Benefits from Green Bonds

Green bonds are already benefitting people around the world on local and global scales. If greenwashing is reduced they have the potential to be an even more valuable weapon in the fight against climate change. Green bonds issued by development banks and IFI’s are particularly important for developing countries as poorer people will be disproportionally affected by climate change. Such bonds will mostly help to fund local scale projects helping people adapt to harsher conditions. On a more global scale, green bonds issued by governments and corporations will help to increase investments into green technologies. With such increases in investments we can hope to see innovation in renewable energy, energy efficiency, pollution prevention, and other exciting areas. With the necessary global cooperation, green bonds will be a vital component in the fight against climate change.

In recent years the gravity of the threats posed by climate change have become more obvious than ever before. Likewise, it has become glaringly obvious that everyone has a part to play in the fight against climate change. This includes the financial sector. CliFin will become increasingly important in shifting incentives to drive sustainable development. The green bond is a relatively recent development within the financial sector and is already causing optimism and enthusiasm amongst investors. Still, greenwashing prevents green bonds from reaching their full potential in the fight against climate change as the phenomena reduces confidence in the market for green bonds. The key to eliminating greenwashing is to create a global consensus on criteria for a green label. Such criteria should be weary of being too restrictive or discriminatory, and should instead promote values such as transparency and disclosure amongst issuers to ease the minds of investors. Until such criteria are established, all actors in the green bond market have a valuable role to play in optimizing the market’s efficiency.

Works Cited

“10 Years of Green Bonds: Creating the Blueprint for Sustainability Across Capital Markets.” World Bank, www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/03/18/10-years-of-green-bonds-creating-the-blueprint-for-sustainability-across-capital-markets.

Ahmad, Rehan, and Yuzo Yamaguchi. “Investors Applaud China’s Plan to Ban Clean Coal from Green Bond Financing.” Spglobal.com, S&P Global, 9 Sept. 2020, www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/investors-applaud-china-s-plan-to-ban-clean-coal-from-green-bond-financing-60257794.

“Bonds and Climate Change: The State of the Market 2018.” Climate Bonds Initiative, 29 Jan. 2019, www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/bonds-and-climate-change-state-market-2018.

Brown, Phil. Green Bond Comment, June – Of Repsol and Reputation. Environmental Finance, 7 June 2017, www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/green-bond-comment-june-of-repsol-and-reputation.html.

Böhringer, Christoph. “Measuring the Immeasurable: A Survey of Sustainability Indices.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2006, doi:10.2139/ssrn.944415.

“CHINA GREEN BOND MARKET 2019 RESEARCH REPORT.” Climatebonds.net, Climate Bonds Initiative, 2019, www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_cbi_china_report_en.pdf.

“COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS.” Eur-Lex.europa.eu, European Commission, 19 Oct. 2020, eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:91ce5c0f-12b6-11eb-9a54-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_2&format=PDF.

“Comparing China’s Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue and the Green Industry Guiding Catalogue with the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy (Part 1).” Climatebonds.net, Climate Bonds Initiative, Sept. 2019, www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/comparing_chinas_green_definitions_with_the_eu_sustainable_finance_taxonomy_part_1_en_final.pdf.

“Consultation on the Renewed Sustainable Finance Strategy.” Ec.europa.ec, European Commission, 10 Feb. 2021, ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/finance-2020-sustainable-finance-strategy_en.

“Disclaimer.” Homepage, 9 Apr. 2019, www.eib.org/en/investor_relations/cab/index.htm.

“EU Green Bond Standard.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, 23 Apr. 2021, ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-green-bond-standard_en.

“Final Report 2018 by the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, Jan. 2018, ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/180131-sustainable-finance-final-report_en.pdf.

“THE GREEN BOND MARKET IN EUROPE 2018.” Climatebonds.net, Climate Bonds Initiative, 2018, www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/the_green_bond_market_in_europe.pdf.

“GREEN BOND PRICING IN THE PRIMARY MARKET: January – June 2020.” Climatebonds.net, Climate Bonds Inititative, 2020, www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi-pricing-h1-2020-21092020.pdf.

“Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds.” Icmagroup.org, International Capital Markets Association, June 2021, www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2021-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2021-140621.pdf.

“Green Bonds.” Enel.com, Enel Group, www.enel.com/investors/investing/sustainable-finance/green-bonds.

“Green Bonds.” World Bank, The World Bank, 2021, treasury.worldbank.org/en/about/unit/treasury/ibrd/ibrd-green-bonds#2.

“Harmonized Framework for Impact Reporting.” Thedocs.worldbank.org, International Capital Markets Association, Dec. 2020, thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/47d9c186d2240c33c80132aca47b5737-0340022021/original/Handbook-Harmonized-Framework-for-Impact-Reporting-December-2020-151220.pdf.

“In Response to Accusations That Enel’s SDG Bond Was Greenwashing.” Environmental-Finance.com, Environmental Finance, 31 Oct. 2019, www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/in-response-to-accusations-that-enels-sdg-bond-was-greenwashing.html.

Liu, Shuang. “Will China Finally Block ‘Clean Coal’ from Green Bonds Market?” Wri.org, World Resources Institute, 29 July 2020, www.wri.org/insights/will-china-finally-block-clean-coal-green-bonds-market.

Otek Ntsama, Ursule Yvanna, et al. “Green Bonds Issuance: Insights in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, vol. 6, no. 1, 2021, doi:10.1186/s40991-020-00056-0.

Pronina, Lyubov, and Tom Freke. “Why Bonds Good for the Earth Now Carry a ‘Greenium.’” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 30 Oct. 2020, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-30/why-bonds-good-for-the-earth-now-carry-a-greenium-quicktake.

“Renewed Sustainable Finance Strategy and Implementation of the Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, 5 Aug. 2020, ec.europa.eu/info/publications/sustainable-finance-renewed-strategy_en.

“‘Second Opinion’ on World Bank’s Green Bond Framework.” Thedocs.worldbank.org, CICERO, 5 May 2015, thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/917431525116682107-0340022018/original/CICEROsecondopinion.pdf.

Shishlov, Igor, et al. “Beyond Transparency: Unlocking the Full Potential of Green Bonds.” Cbd.int, Institute for Climate Economics, June 2016, www.cbd.int/financial/greenbonds/i4ce-greenbond2016.pdf.

“The State and Effectiveness of the Green Bond Market in China.” Climatepolicyinitiative.org, UK Government, June 2020, www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The_State_and_Effectinevess_of_the_Green_Bond_Market_in_China.pdf.

“Sustainability.” United Nations, United Nations, www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability.

“TEG REPORT PROPOSAL FOR AN EU GREEN BOND STANDARD.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, June 2019, ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/190618-sustainable-finance-teg-report-green-bond-standard_en.pdf.

T. Ehlers and F. Packer ‘Green Bond Finance and Certification’, Bank for International Settlements, 2017.

“United Nations Conference on Environment & Development Rio De Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992.” Sustainabledevelopment.un.org, United Nations, sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf.

“USABILITY GUIDE TEG PROPOSAL FOR AN EU GREEN BOND STANDARD.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, Mar. 2020, ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/200309-sustainable-finance-teg-green-bond-standard-usability-guide_en.pdf.

“Vigeo Eiris Provides Second Party Opinion for Enel’s Innovative Sustainability-Linked Financing Framework.” Vigeo-Eiris.com, Vigeo Eiris, 12 Oct. 2020, vigeo-eiris.com/vigeo-eiris-provides-second-party-opinion-for-enels-innovative-sustainability-linked-bond/.

von der Leyen, Ursula. “State of the Union 2020: Letter of Intent to President David Maria Sassoli and to Chancellor Angela Merkel.” Ec.europa.eu, European Commission, 16 Sept. 2020, ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/state_of_the_union_2020_letter_of_intent_en.pdf.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/03/18/10-years-of-green-bonds-creating-the-blueprint-for-sustainability-across-capital-markets

[2] https://www.eib.org/en/investor_relations/cab/index.htm

[3] www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/bonds-and-climate-change-state-market-2018

[4] https://jcsr.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40991-020-00056-0

[5] https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability

[6] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

[7] https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0921800907002029?token=4505C4EA0FBD8AB1E6D580E0786C65F71A3DB993AB85C5BAD0260F882861D97875F4394FA5D1AA4C8E9E9020D4DD1483&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20210622165310

[8] https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/green-bond-comment-june-of-repsol-and-reputation.html

[9] https://www.cbd.int/financial/greenbonds/i4ce-greenbond2016.pdf

[10] https://treasury.worldbank.org/en/about/unit/treasury/ibrd/ibrd-green-bonds#2

[11] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/917431525116682107-0340022018/original/CICEROsecondopinion.pdf

[12] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/47d9c186d2240c33c80132aca47b5737-0340022021/original/Handbook-Harmonized-Framework-for-Impact-Reporting-December-2020-151220.pdf

[13] https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2021-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2021-140621.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] T. Ehlers and F. Packer ‘Green Bond Finance and Certification’, Bank for International Settlements, 2017.

[17] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/180131-sustainable-finance-final-report_en.pdf

[18] https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/sustainable-finance-renewed-strategy_en

[19] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/190618-sustainable-finance-teg-report-green-bond-standard_en.pdf

[20] https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-green-bond-standard_en

[21] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/200309-sustainable-finance-teg-green-bond-standard-usability-guide_en.pdf

[22] Ibid.

[23] https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/finance-2020-sustainable-finance-strategy_en

[24] https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-green-bond-standard_en

[25] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/state_of_the_union_2020_letter_of_intent_en.pdf

[26] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:91ce5c0f-12b6-11eb-9a54-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_2&format=PDF

[27] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/the_green_bond_market_in_europe.pdf

[28] https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/in-response-to-accusations-that-enels-sdg-bond-was-greenwashing.html

[29] https://www.enel.com/investors/investing/sustainable-finance/green-bonds

[30] https://vigeo-eiris.com/vigeo-eiris-provides-second-party-opinion-for-enels-innovative-sustainability-linked-bond/

[31] https://www.wri.org/insights/will-china-finally-block-clean-coal-green-bonds-market

[32] https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The_State_and_Effectinevess_of_the_Green_Bond_Market_in_China.pdf

[33] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_cbi_china_report_en.pdf

[34]https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/comparing_chinas_green_definitions_with_the_eu_sustainable_finance_taxonomy_part_1_en_final.pdf

[35] https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/investors-applaud-china-s-plan-to-ban-clean-coal-from-green-bond-financing-60257794

[36] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_cbi_china_report_en.pdf

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-30/why-bonds-good-for-the-earth-now-carry-a-greenium-quicktake

[40] https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi-pricing-h1-2020-21092020.pdf